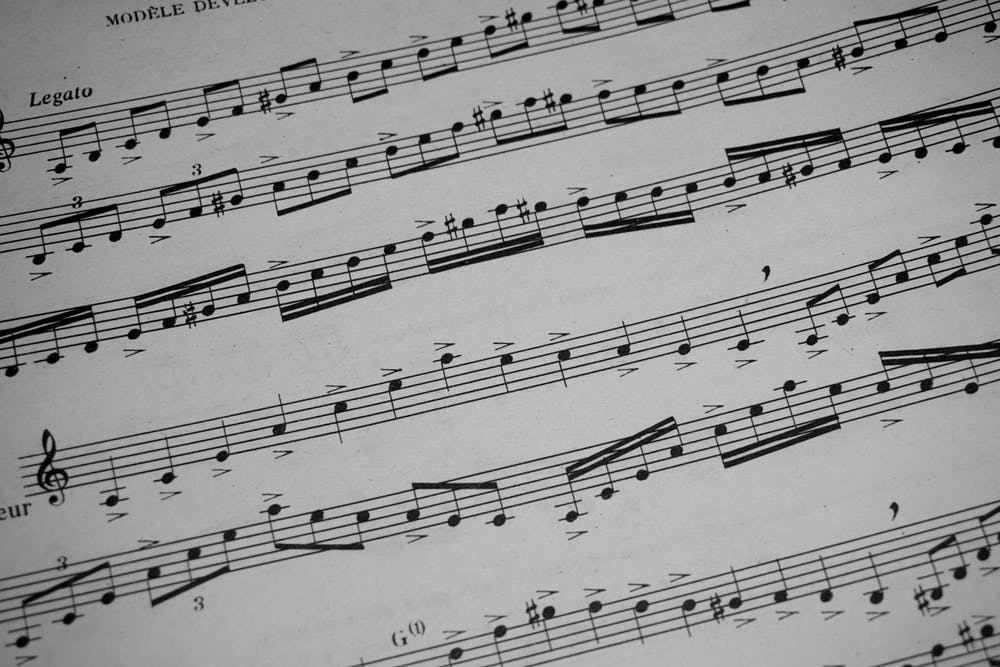

“How would you practice this?” I asked my private flute student. She’s in ninth grade, very talented, and currently working through the Anderson Opus 24 Etude book. (Flutists will know the one.) “What would you do first?”

She told me that she’d play through the first few lines very slowly. Then, once she’d gotten a feel for the piece, she’d stop and do what I’d always prompted her to do with a new piece: write focus keywords at the top of the page based on what she’d heard. We took a few minutes for her to complete this step of the process, and at that point she knew what she was up against with the etude– the challenges, the musical elements.

“Then what?” I asked her.

She hesitated. “Then I’d just… play it. Until it got better.”

And that was when I realized I’d failed to teach her something crucial: how to plan her practice. I’d done an incomplete job. I’d taught her how to set herself up for success right at the start, but hadn’t shown her how to work through the middle of the process. I’d assumed she knew how because, in the three years I’d been teaching her, she almost always produced a finished piece on her own. But things were starting to get harder, and now she needed more tools.

What would I do if this was a writing student instead of a flute student? I thought. What would I do if it was my writing practice?

If it was me practicing, I would have made a plan. I’d start with a list of things I wanted to accomplish. Then I might estimate how long it would take me to do each item. I’d decide what to focus on for each practice day that week. Then, when I began my practice, there would be no guesswork, no “just play until it gets better.” I would already have a target and a goal, and when the session was over I’d know what I achieved.

There is a difference between practicing an instrument and writing something from scratch: the musician will never sit down to the blank page. There will be notes put there by a composer (whose practice was probably more similar to the writer’s). Yet the concept is the same. If you don’t know what you’re going to practice, you won’t use your time as wisely.

This is what I told my student, and added that I’d make her a worksheet to help guide her through the process. As she packed up her flute, I thought about how I would have practiced at her age– probably exactly the way she was practicing now. Then again, I didn’t have a teacher to teach me anything different, other than my ninth-grade band teacher, who finally pushed me to actually practice rather than just play through things. My flute student won’t have the same excuse– at least not anymore!

How simple, but how profound. Beginnings are comparatively easy. It’s that long, slow, slog in the middle that gets us. I’m going to think about how this applies to writing.